A BIT OF MAINE BATEAU HISTORY

OK! SO, THE ABOVE QUOTE FROM THE MOVIE “JAWS” IS NOT QUITE ACCURATE!

HOPEFULLY, YOU’LL GET MY DRIFT… SO, READ ON!

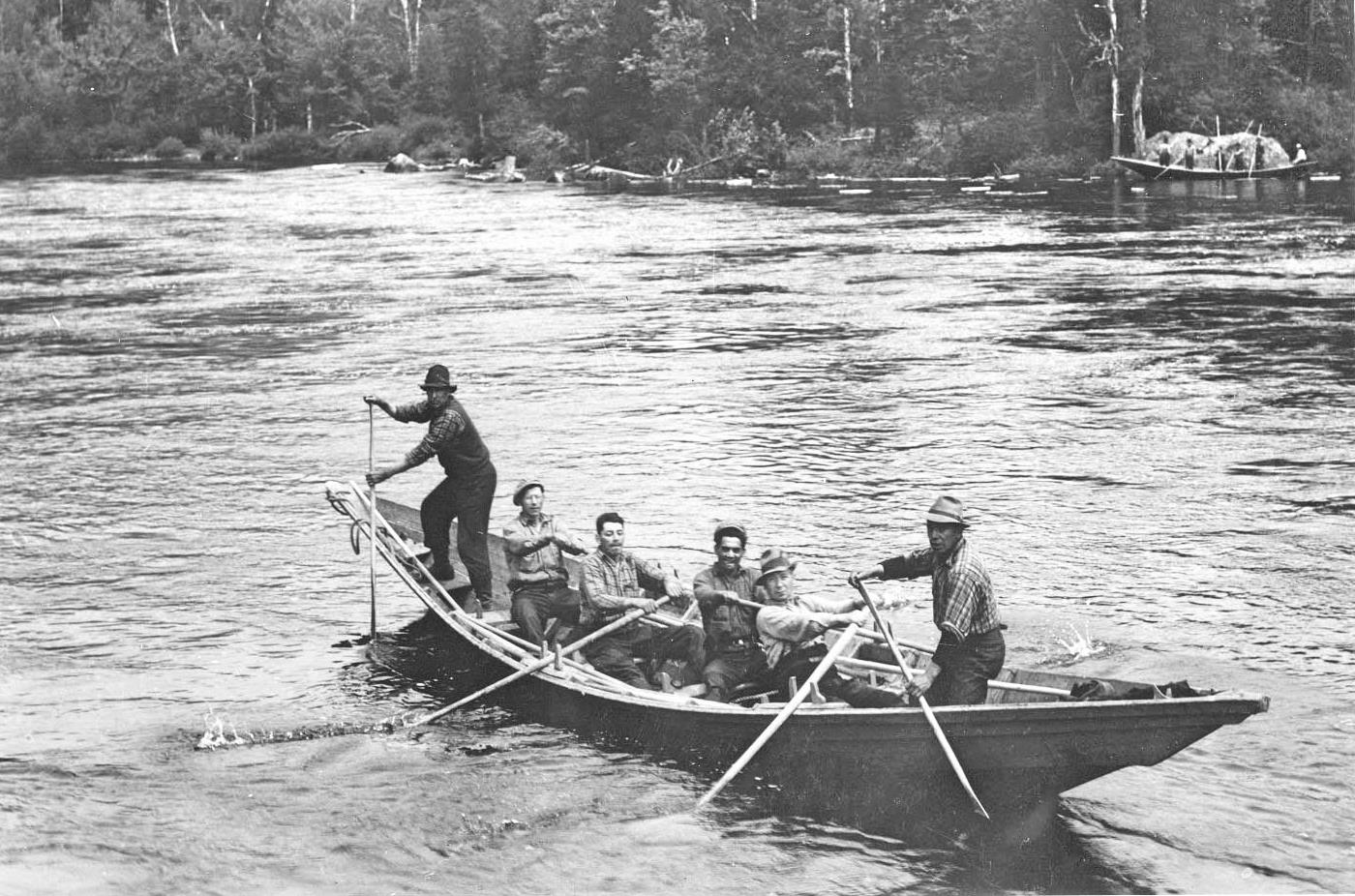

Sitting under one of the Museum’s pavilions is a bateau. Bateau is the French word for boat. The bateau is a flat-bottomed boat without a keel and is approximately 15 to 30 feet in length. It is 4 feet wide and sharply pointed at both the bow and the stern (similar to the bow of a canoe). Twelve-foot poles with an iron point are used to operate and steer the boat. At times, oars are used to propel the boat as well.

The bateau was introduced to North America in the early 1600’s by French trappers. The small boat required only one or two crewmen to operate. The shallow draft and flat bottom of the bateau worked well in maneuvering the streams and rivers throughout the interior woods of the northeast. The French trappers could easily transport their pelts and goods to nearby trading locations.

The bateau had numerous uses in the Maine woods beyond transporting pelts. The small boat was used to transport military supplies to remote areas for both colonial and British troops. In the early days of the American Revolution, Benedict Arnold

ordered hundreds of bateaux to be built, carried and used across Maine’s remote wilderness to help achieve his secret mission to seize Quebec City! (Arnold did not succeed).

Early Europeans were stunned by the sheer volume of trees in New England forests. Acres and acres of birch, spruce and most importantly pine trees were readily at hand. England’s King George III began to reserve large tracts of Maine’s forests through the “Broad Arrow” policy. This policy forbade North American colonists from cutting down the largest trees especially white pine trees. King George III recognized the importance of maintaining strong commercial and naval fleets. Having an “endless” supply of white pine dedicated for ship masts could maintain Great Britain’s economic and political worldwide dominance.

Harvesting the forest for economic development beyond mastheads and ship building did not occur until well after the American Revolution. As British oversight waned and the colonial population increased and expanded westward, demand for wood products such as barrels, shingles, planking for homes and ships exploded. The demand for more wood products required larger amounts of felled trees to be delivered to the wood mills for processing. How would those trees get to the mills situated along Maine’s numerous rivers? By simply floating them down a nearby river! Well, maybe not simply…

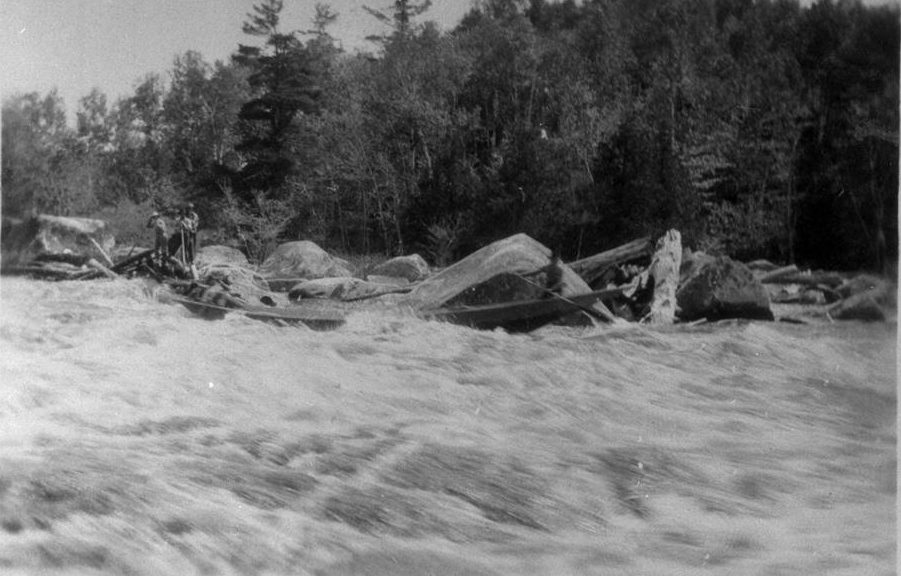

Floating large logs down Maine’s Penobscot, Androscoggin, Saco, and Kennebec rivers was no easy task! “Log drives” as they were called back in the 1800’s, began in the winter months. During the cold and snowy months loggers would cut, transport (by horse), and stockpile thousands of trees along the riverbanks. Winter conditions provided an easier way to move felled trees to the riverbanks. Once the snow and ice melted in late spring the logs would be dumped into the rivers and floated to the mills.

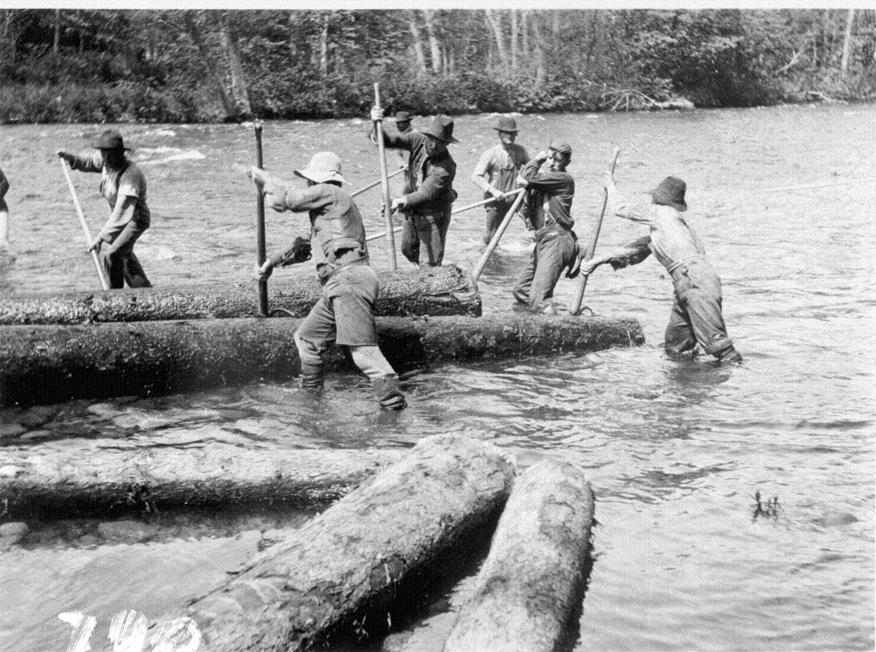

As we know, floating down any of Maine’s rivers requires the ability to avoid obstacles such as large rocks, shallow banks and trees. As one can imagine, large cut trees would become hung up on these types of obstacles and cause huge log jams! How would these masses of snarled trees become untangled?

Enter the bateau and some very brave men with pike poles, cant dogs and peaveys!

Check out the pictures and tell me you wouldn’t want a bigger bateau!

Credits: Patten Lumbermen’s Museum, Maine History On-Line, The Maine Boomhouses, MaineBoats.com.